OAAPN 2024 Conference

JAAPN ARTICLE:

Medical aid in dying: The role of the nurse practitioner

Kathryn A. Harrawood, MSN, NP, AGNP-C (Graduate School Alumna)

ABSTRACT

Medical aid in dying (MAID) is a practice that has been expanding in the United States over the past few decades. As it becomes a viable option for a growing portion of the American population, nurse practitioners (NPs) need to be prepared to engage in conversation with patients about the practice. Although historically only physicians were able to participate in MAID, the role has recently expanded to include additional advanced practice providers, including NPs. Reviewing the history of MAID and examining how current legislation affects clinical practice can support the NP’s ability to educate and counsel patients about the option. Identifying specific areas in which MAID providers report needing additional training and support can help providers work toward delivering the highest quality patient

care possible. As MAID becomes accessible to greater numbers of people, NPs need to be prepared to talk to patients who are navigating serious, life-limiting illnesses about the possibility of MAID.

Introduction

Medical aid in dying (MAID) refers to the process by which a mentally competent adult individual who has a life-limiting prognosis can request a lethal dose of medication from a provider (Gerson et al., 2020). In the United States, the medication must always be administered by the individual, without assistance from the prescribing provider or any other person. In other countries, the term MAID is also used to describe the direct administration of a lethal medication by a health care provider at the

patient’s request (Mroz et al., 2021). Various phrases have been used historically to describe this phenomenon, including “physician-assisted death,” “physician-assisted suicide,” and “death with dignity” (Pope, 2020). For this article, the term “medical aid in dying” will be used to refer to the process by which an individual with a life-limiting illness can obtain a lethal dose of medication from a provider with the intention of ending their life.

Medical aid in dying has been a controversial topic for the past few decades, in both health care and popular culture, because of the strong opinions it provokes about the concepts of the sanctity of life and the right to die. Nevertheless, MAID services have been expanding significantly over the past two decades as a result of legalization in many parts of the United States and other countries around the world (Mroz et al., 2021). As a result, the number of health care providers who practice in a system that offers MAID is increasing. In the United States, physicians were traditionally the only health

care providers legally allowed to participate in MAID at the exclusion of other prescribing providers (Stokes, 2017). Recently, the roles and responsibilities of MAID providers have been extended beyond physicians to include nurse practitioners (NPs) and other health care providers (Singer et al., 2022). During this time of continued growth of MAID services, it is important for NPs to understand the current scope of their role and look ahead to anticipate potential implications for NP practice in the future.

Expansion of services

Medical aid in dying was first legalized in the United States through a ballot measure in 1994 in the

state of Oregon (Pope, 2020). Since then, MAID has been legalized in 10 other states and territories including Washington state, Montana, Vermont, California, Colorado, Washington D.C., Hawaii, New Jersey, Maine, and New Mexico (Compassion & Choices, 2023). The path to legalization in the United States varied from place to place, including legislative action, judicial decisions, and additional ballot measures. The rate at which MAID is being legalized has increased recently with seven new states

and territories approving MAID between 2015 and 2021, resulting in 25% of the population of the United States currently having access to services (Pope, 2020). In 2020 18 additional states considered legislation around MAID, demonstrating the potential for wider expansion of access to MAID in the United States (Pope, 2020).

Ethical considerations

As MAID becomes an increasingly accessible resource, there is continued debate among health care providers about the ethics of assisted dying. Advocates for MAID argue that the practice supports patient autonomy, relieves suffering, and is a safe medical practice (Dugdale et al., 2019). Opponents of MAID express concerns related to beliefs around the sanctity of life, fear of a “slippery slope” leading to involuntary euthanasia, and inadequate exploration of alternative options such as palliative and hospice care (Dugdale et al., 2019). Many clinicians look to professional organizations for guidance when faced with complicated clinical questions. In a 2013 position statement, the American Nurses Association (ANA) argued against nursing involvement in MAID, asserting that assisted dying goes against the fundamental goals of nursing and violates the social contract that nurses have with society (Vogelstein, 2019). Since the rapid expansion of MAID, the ANA released a revised statement in 2019 to acknowledge that an increased number of nurses, including registered nurses and NPs, are involved in providing MAID services. The revised position statement neither endorses nor condemns MAID but seeks to support nurses in their ability to have unbiased end-of-life conversations with patients and advocate for palliative care and hospice services (ANA Center for Ethics and Human Rights, 2019). The Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association (HPNA) 2017 position statement reiterates the nursing responsibilities laid out by the ANA and goes further to provide step-by-step guidance for NPs to respond to requests for hastening death, including providing information about MAID where appropriate (HPNA, 2017). Neither the ANA nor HPNA specifically endorses MAID, which creates a complicated landscape for nurses to navigate in places where MAID is legal.

Clinical implementation

Looking back at the history of MAID in the United States, Al Rabadi et al. (2019) reviewed the use of MAID in Oregon (from 1998) and Washington state (from 2008) through 2017. During the combined 28 years of available MAID data, there were 3,368 prescriptions written that resulted in 2,558 patient deaths. Of all reported deaths, 81% occurred at home, and the prescriber was present in 9.7% of the cases. Starting at the time of medication administration, the median amount of time to achieve a comatose state was 5 min, with a median of 25 min to the time of death. Complications during the MAID process were rare, only affecting 4% of patients; the most common complications included difficulty ingesting the medication and regurgitation of medication. Most people who received prescriptions had a terminal cancer diagnosis, followed by diagnoses including neurological illness, lung disease, heart disease, and other illnesses. Most people seeking MAID were college-educated, non-Hispanic, White indi- viduals older than 65 years with equal numbers of men and women represented. Of all MAID patients, 88.5% had health insurance, and most were enrolled in hospice at the time of the request, 87.8% in Oregon and 64.2% in Washington. The most common reasons documented for requesting MAID included loss of autonomy, impaired quality of life, and loss of dignity.

Although there is some variation in the rules and regulations around MAID in different states, the core

concept and safeguards are consistent throughout the United States. To be eligible for MAID, the patient must be older than 18 years, have a terminal diagnosis with a prognosis of six months or less, demonstrate decision- making capacity, and be able to self-administer the medication (Pope, 2020). The prescribing provider must work with a second consulting provider to ensure that the patient meets the eligibility criteria and is acting voluntarily and provide education about alternative treatment options (Pope, 2020). Physicians were the only health care providers able to participate in MAID in the United States until New Mexico’s MAID legislation was passed in 2021, which allowed both NPs and physician assistants (PAs) to act as prescribing and consulting providers (Singer et al., 2022). Other states where MAID is being practiced have considered expanding the provider role to include NPs and PAs but have not yet passed legislation to support that effort (Singer et al., 2022). Given the potentially expanding inclusion of NPs as MAID providers, a close examination of the role of the NP in the MAID process is

warranted.

Nurse practitioner participation in medical aid in dying

Singer et al. (2022) surveyed specialty advanced practice providers (APPs) in Washington state to assess their willingness to participate in MAID. The survey respondents included NPs and PAs who worked mostly in medical oncology, hematology, transplant, and supportive care. Although MAID has been legal in Washington since 2008 with physicians designated as the only eligible providers, an amendment to expand that role to other APPs was considered but ultimately not passed in 2021 and 2022 (Singer et al., 2022). Of all APPs surveyed, 90.9% either agreed or strongly agreed that MAID should be legal, and the majority agreed that APPs should be included as eligible providers. Regarding their personal participation, 50.6% of respondents reported willingness to participate in MAID, whereas 40.3% were unsure and 9.1% were unwilling to participate (Singer et al., 2022).

Because New Mexico has legalized the practice of NPs providing MAID, further research is required to assess how the role of the NP in MAID develops over time. Given the history of over-representation of NPs in advance care planning, NPs may be responsible for a substantial amount of MAID provision. In a West Virginia study, Constantine et al. (2021) found that NPs filled out almost twice as many advance directive forms as physicians and were more likely to include preferences for comfort measures and do-not-resuscitate orders. In a similar study in Oregon, the percentage of advance directives signed by NPs

rose from 9% to 11.9% between 2010 and 2015 (Hayes et al., 2017). Additionally, research from Vermont has shown that most patients initiate a conversation about MAID with their primary care providers, a field in which NPs have a growing presence (Landry et al., 2020). Given that NPs have exhibited a propensity toward discussions about end of life, it is likely that NPs in New Mexico will be included in MAID provision in a significant way. If other states legalize NP participation in MAID, having data from

New Mexico will provide existing MAID teams with guidance about the most effective way to incorporate NPs into the practice.

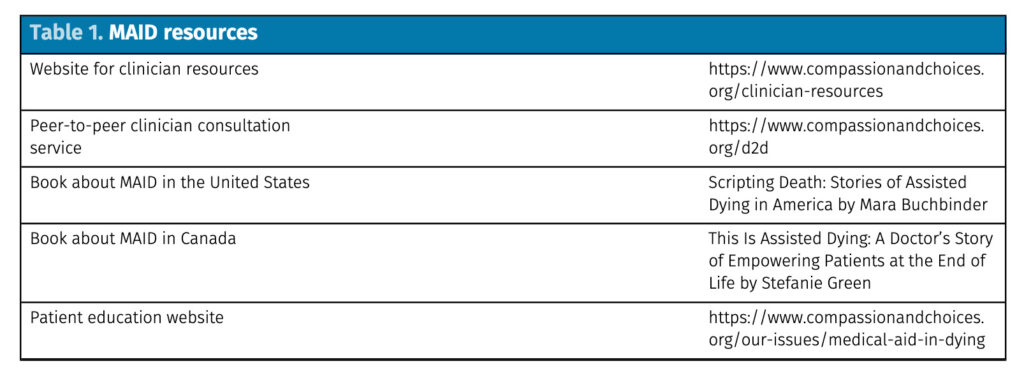

Although an NP’s involvement in MAID is fundamentally guided by state laws and organizational policies, the provider’s own preference plays a role as well. For NPs whose patients are interested in MAID but are unable to receive services within the NP’s home state or institution, the NP can provide the patient with educational resources (Table 1) and a referral to an organization that provides MAID. Historically, MAID laws required patients to be a legal resident of the state where services were provided,

but recent legislative changes in Oregon and Vermont have removed that requirement, expanding access to MAID to nonresidents as well (Span, 2023). For NPs who are uninterested in or opposed to engaging with MAID, the choice to opt out of providing services is a legally protected option (Brassfield et al., 2019). After the legalization of MAID in Canada, many physicians who supported the legislation reported conscientious objection to participating in the practice. Of interest, most physicians cited the associated emotional burden and administrative work as reasons to opt out, rather than moral opposition to the practice itself (Bouthillier & Opatrny, 2019). Across the United States, NPs have the option to discuss MAID with patients but are not penalized for opting out of MAID discussions or services.

Provider training and support

After Vermont’s MAID legislation passed in 2013, health care providers and systems found themselves in the position of building a clinical practice based on the new law. Although the legislation clearly details eligibility criteria, safeguard measures, and documentation standards, it does not provide clinical guidance on prescribing, educating patients, and determining patient competency (Buchbinder et al., 2019). In a survey of 37 MAID providers in Vermont, physicians reported inadequate education, training, and support around MAID, prompting them to seek information from professional networks and advo-

cacy organizations (Table 1). In practice settings where MAID was institutionalized with clear clinical guidelines, providers reported feeling less burdened by their clinical duties (Buchbinder et al., 2019)

Vermont physicians reported needing support around MAID prescribing, specifically which medications to prescribe and at what doses (Buchbinder et al., 2019). In addition, providers reported challenges finding out the cost of prescribed medications and if health insurance would cover any of the prescription drug cost. In a survey of specialty providers in Vermont, 37.4% reported not having enough information to complete paperwork and write prescriptions for MAID (Landry et al., 2020). Questions around prescribing highlight the opportunity to dialog with existing MAID programs in other states and

foster interdisciplinary collaboration between prescribing providers and pharmacists. Regarding patient

counseling, 51.4% of Vermont providers reported needing more resources to provide counseling and expressed a desire for more formalized training around MAID counseling (Landry et al., 2020). Because MAID is a medical practice that results in ending a patient’s life, it is paramount that providers feel both knowledgeable and comfortable discussing the practice with patients.

Interviews with registered nurses and NPs who had experience implementing MAID in Canada highlighted some key elements for successful development of MAID as a new clinical practice (Pesut et al., 2020). The data suggest that clear clinical guidelines, interdisciplinary teamwork, and institutional support are necessary for MAID programs to function well. Specific factors that contributed to successful MAID programs include having an organized referral system, an adequate amount of providers, access to required paperwork, and a system to share patient information between primary and second- ary providers (Pesut et al., 2020). Unfortunately, clinicians in Canada and the United States have consistently reported a lack of clear clinical guidelines and institutional support around MAID.

The current body of literature highlights the gap that exists between MAID as a concept versus a clinical prac- tice. Compared with the robust number of articles published examining the ethics of MAID and the path to legalization, there is a relative lack of research examining MAID policy, provider training, and patient experience. Richardson (2022) asserts that because nursing policy related to MAID is “limited and highly variable” (p. 1), registered nurses and NPs do not have the guidance needed to provide the best care. In addition, there is a paucity of research focused on provider training and professional support, which are required elements for quality patient care. More research on specific MAID procedures and patient outcomes is needed to facilitate improvement and growth in the field.

Conclusion

For Acknowledgements and sources, download the original PDF: Medical Aid in Dying (MAID) – The Role of the Nurse Practitioner

Menu

- Welcome OAAPN Conference Attendees

- Register Now: The Role of the APRN in MAID and End of Life Care Advocacy virtual event

- JAAPN: The Role of the Nurse Practitioner

- OAAPN Fact Sheet: Medical Aid in Dying

- ANA Position Statement: The Nurse’s Role

- Dr. Barbara Daly in the Dayton Daily News

- Dr. Maryjo Prince-Paul: Patient-Centered End-of-Life Care

- ANA-Ohio Profile – Exec. Dir. Lisa Vigil Schattinger, MSN, RN

- Online Petition